At 82, he is a savvy mogul of digital media, with 2.9 million Twitter followers, 10 million Facebook followers and his Oh Myyy network of digital properties, which offers a mix of news, politics and videos. Such views will not be surprising to Takei’s millions of fans on social media, where he expresses his opinions daily and sometimes hourly. “Now, their children are torn away from them as examples, so that other desperate people won’t follow in their footsteps,” he says. “It’s a new low,” he says, noting that during his years of incarceration, “we were always intact as a family.”

Nor did it apply to citizens of German or Italian origin, “because they looked like the rest of America,” Takei says.īut while he is heartened by progress toward racial equality, Takei is outraged by the current treatment of asylum seekers at the southern border, and particularly by the separation of families and children.

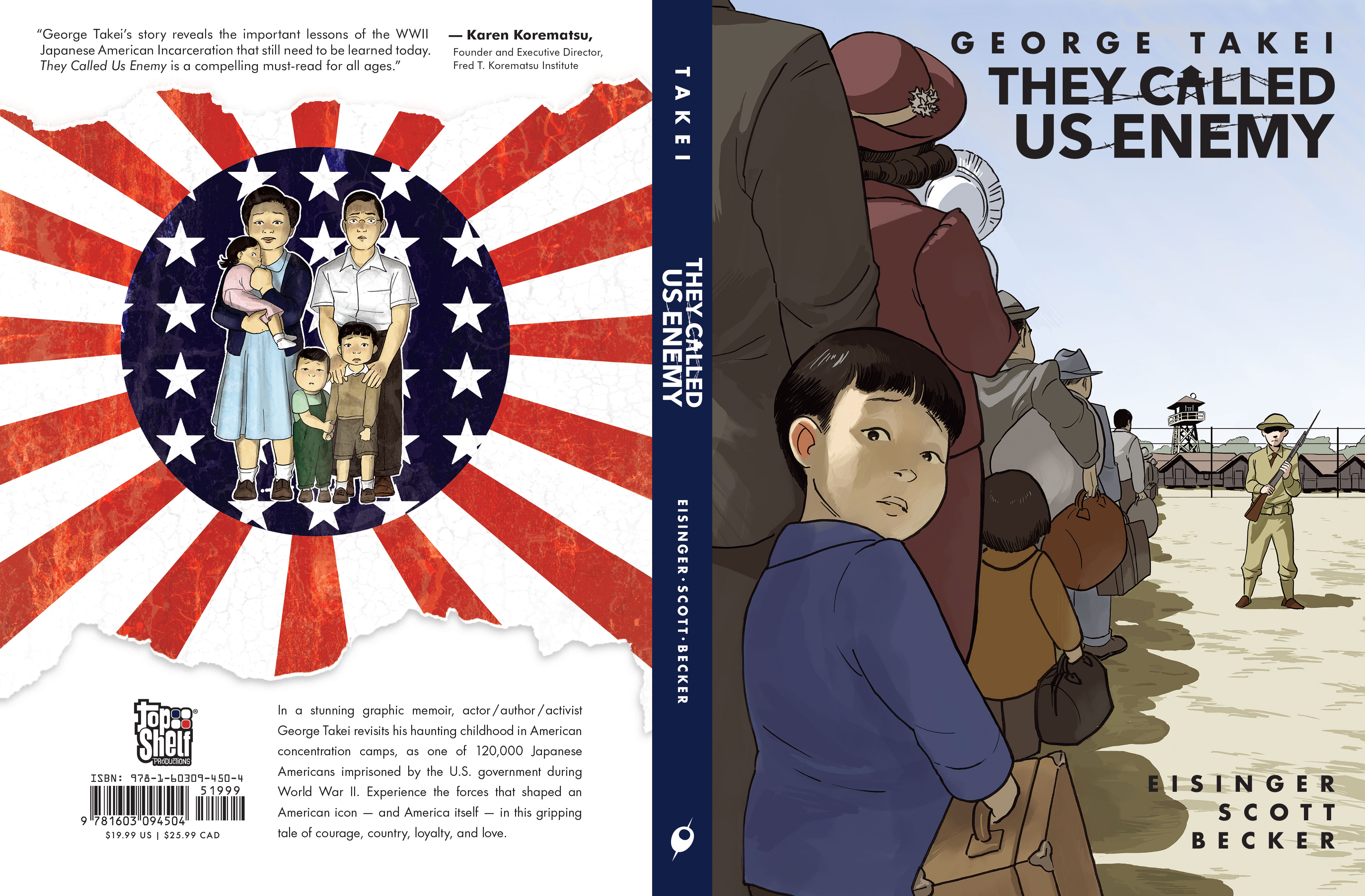

It was a punishment that did not apply to residents of Hawaii, where they were crucial to the economy. Takei is an optimist who sees progress since those wartime years when there was little resistance to President Franklin Roosevelt’s order to lock away thousands of Japanese American citizens and legal residents. “They obviously didn’t know the English language.” He specifically cites Question 28, which was worded in an ambiguous way that forced Japanese Americans to either admit they had been loyal to the emperor of Japan or be labeled as “disloyals.” “It was an outrageous and ignorant question,” Takei says. Takei expresses disbelief at how government bureaucrats mangled the questionnaire that landed him and his family in a prison camp surrounded by three rings of barbed-wire fencing and patrolled by tanks. “Think of that: the arrogance of demanding loyalty when they have, first of all, impoverished you, and then imprisoned you, and now, because it fits their need and convenience.” In 1944, the family was moved to the high-security Tule Lake Segregation Center in remote Northern California after Takei’s parents were declared so-called disloyals for refusing to answer two notorious questions in the affirmative.Īlmost 75 years later, Takei is still angry about it. “I wanted to capture the reality of this strange new world that I was transported to, but at the same time how my parents felt and the anguish that they were going through.” “There are two parallel stories,” Takei says. But the illustrated book exposes the humiliation and financial hardship suffered by his parents as they struggled to adjust to their new lives and survive intact as a family. Takei remembers Arkansas as a “fantastical, magical” new landscape where trees grew out of swamps and he saw his first snowfall. After a few months at Santa Anita, the family was sent by train to the Rohwer relocation camp in rural Arkansas.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)